Director Fateema Al-Hamaydeh Miller: on Homeland, Hope & a Free Palestine.

Palestinian-Canadian filmmaker talks unearthing the detriments of colonization on our collective memory of homeland through recent short film, Mawtini.

This week, I’m honored to welcome one of the most important artistic voices in Canada today—someone who has brought The Produced an abundance of knowledge, art, hope, and love.. Fateema Al-Hamaydeh Miller, a Palestinian-Canadian filmmaker, has seen her work embraced across the globe. Her latest short film, Mawtini (My Homeland), follows a young Palestinian girl who finds companionship with an older Indigenous woman. Together, they plant a guerrilla garden—an act of quiet resistance—sparking conversations on land sovereignty, identity, and the meaning of home.

I find myself returning to this conversation—again and again. Perhaps to grasp at hope within hopelessness, to reckon with the fragility of optimism. Or perhaps to make sense of the world through the eyes and voice of an artist who is both relentless and tender, unflinching in addressing the crises we face, even as the world turns away from the face of genocide.

From checking in with one another, to speaking about making Mawtini in the days after October 7th, to the self-fueled mechanics of continuing to create and remain when the world tells you not to—this conversation is a reminder that we are okay. That the work we do as artists is not just necessary, but foundational—to keeping hope alive and uncovering truth.

The Produced: Hi Fateema, thank you for being here. What is your headspace right now?

Thank you for starting here. Navigating this space as a Palestinian living in the West feels weird. Life moves on here, the industry moves on here, and yet, there aren’t enough spaces that uplift diverse artists. And even when they exist, few are brave enough to hold space for Palestine and acknowledge the realities of what’s happening. It’s an ongoing journey. This past year has had so many phases of trying to grapple with the genocide, which is impossible for all of us to even begin to understand why this much violence is possible.

How are you doing?

My body felt so burnt out from this year. It reminded me that I need to take care of myself, and that within itself is a political act. Where I’m at now is going back to basic self-care. Making sure I’m eating, trying to get good sleep, and just being gentle. I’m reminding myself that there’s a whole community carrying this with me, so it’s so important to recharge and take care of ourselves to keep fighting. The dissonance of being in the world here in the West is grating. You feel like an alien sometimes, like, how is everyone just normal? And instead of trying to understand that, I’m going internal, focusing on my community, my friends, and the things that recharge me.

That’s where I’m at.

Thank you so much for sharing and for opening your heart in this conversation. Your short film, Mawtini (My Homeland), is out in the world now, especially in this fraught time. But you wrote the film a while back—how did the story come about?

I started developing the story almost three years ago. It came from reckoning with the reality of being from stolen land, living on stolen land, and questioning my responsibility in both contexts. It’s a strange and dissonant parallel. How do I navigate the ongoing colonization of my homeland, which I can’t return to, while also being part of colonization as a settler here?

What did you realize during the process of reckoning with these histories and your own place within them?

Living in Toronto, I’ve always been drawn to Indigenous stories and feel a deep connection to celebrating and uplifting the work of Indigenous creators. I’m grateful for the friendships I’ve built within that community and for the opportunity to witness and share in their art. Those relationships and conversations with Indigenous artists on Turtle Island, as well as the allyship between our communities, have been profoundly inspiring. Seeing Indigenous Peoples showing up for Palestine and Palestinians showing up for Indigenous causes highlights our shared histories—different in timelines, but deeply connected.

The film began from these reflections and from grappling with the impossibility of ideas surrounding intersectionality and identity being from stolen land and living on stolen land. It’s also a lot of asking questions such as how do you find justice, solace, or community in the face of it?

These intimate interconnections are portrayed in Mawtini through your two characters, Tanya, an Indigenous woman, and Nawal, a Palestinian woman, working on a guerilla garden. This is a beautiful nod to the shared history of Indigenous Peoples. Why was it important for you to intertwine Indigenous identities with nature, gardening, and the land in this story?

I think these big ideas—what it means to live under colonialism, what the path forward looks like for reconciliation or connection to land—are all present in the everyday. These grand concepts play out in tiny, everyday scenarios, and that’s what I was interested in exploring. With Mawtini, I’ve been able to take these big ideas and place them in a small microcosm. For me, living in Toronto, especially with such precarious housing situations, it’s impossible to ignore the housing crisis here. There’s so much insecurity around who gets access to land, and it’s fascinating to see who’s afforded that privilege.

And from your observations, what have you uncovered?

I live in East Chinatown, a neighbourhood defying gentrification, where Vietnamese and Chinese families have been rooted for so long, growing beautiful gardens. But then, you see these young white couples moving in, buying up the “cheaper” homes (cheaper for Toronto), and it’s just...ugh. I have this little ratty balcony with three dead AC machines on it where I try to grow my plants. Meanwhile, I’m looking out at these two backyards.

What do these backyards tell you?

One family has covered their entire lawn with fake turf, and the other has paved over everything. It burns. It makes me burn. Because if I had even a small piece of dirt, it would make me so fucking happy. In a city like Toronto, where property is insanely expensive, it’s near impossible for marginalized people to own land. And when colonizers get access, they just pave it over or cover it with turf. Meanwhile, people who understand and value the land would nurture it, grow things, and find joy in that connection.

It’s the entrenched system.

Exactly. There’s so much bureaucracy tied to colonialism that disconnects us from the land. For example, even in a city, there’s that tiny strip of grass between the sidewalk and the road, and it’s illegal to plant anything there. Wild, right? The system actively cuts us off from the land, from that freedom and joy it gives us.

That’s what Tanya embodies in the film. She’s a total badass. Monique, who played her, was my story editor and deeply involved in the script’s development. She brought so much to that character because she’s a badass in real life too, not just on camera. Watching her and the character push against this system and claim that connection to land feels so powerful.

I want to stay on this train of thought, addressing the system and its corruption. In the film, the building manager, who’s constantly nagging the women to uproot their garden, is an immigrant. What was the intention behind making this character an immigrant rather than, say, a stereotypical white authority figure?

Good question. In the writing process, some people would ask why the building manager, Rodrigo, is an immigrant and not just a white guy. But simplifying the story that way felt off to me.

How so?

Our world is more complex, and white supremacy often uses people of colour to perpetuate its system of violence. The victimized becomes the victimizer, and that’s good news to those who are in the highest power of the system. Rodrigo’s an immigrant trying to make ends meet for his family. He's playing the game, hoping that by following the rules, he might find security or stability. But even if he follows those rules, he won’t "win" — he’s still trapped in the same system. White supremacy doesn’t have to directly enforce its rules because people like Rodrigo, vulnerable and seeking stability, end up taking those roles.

The victimized becomes the victimizer.

And still, you are not afforded any protection for playing by the rules because the rules aren’t created for people like you. Through his character, I wanted to show that all three characters are trapped in the same system, each coping with it in different ways.

When writing and making the story, were there any conversations—whether with community members, friends, or key team members—that left a lasting impact on the narrative or themes of the film?

Before shooting the film, my actors Rena Dine (Nawal), Monique Mojica (Tanya), and I had a lot of Zoom calls for discussions and rehearsals since we were all in different cities. Then we began shooting just one week after October 7th, which was a huge challenge. When we finally had everyone together, it was incredibly valuable to have us all in one place, understanding each other and how everyone was coping. Especially for them to hold space for me as a Palestinian at that point in time—it meant so much.

Going into this film, what did you want to do different from your past projects, given how you’ve shared the context and weight of the story, and the different themes you are trying access to foster conversations through a cinematic language?

With this project, I really wanted to challenge myself visually and take it in a direction that scared me. My last film was very static, stylized in its movements, and used style and humour to create a bit of a barrier between the emotional content. While there was still deeper emotion, the visuals were playful, distancing the audience from the darker side of the story.

For this one, I wanted there to still be humour, but I also wanted to challenge myself to get closer to the actors—closer to their faces. I wanted more movement with the camera, to not be afraid to move it. So, we did a lot more handheld work and close-ups, sitting in silence with the characters and adapting to their movements. We discovered things with the camera as we went, moving around the actors and finding those intimate moments. My DP, Nick Haight, and I looked a lot at the work of Andrea Arnold, an amazing British filmmaker whose work is intimate, beautiful, and always handheld. That was a big inspiration—trying to be brave, vulnerable, and capture individuals more closely than I had before.

Another element that I found to have nourished the intimacy between the audience and the character is Nawal’s room. Can you walk me through the design of that space?

I was incredibly lucky to work with such an amazing production design team. Our main character, Nawal, has a box filled with items that remind her of home, her grandmother, and the land she’s deeply connected to. They worked tirelessly in a short amount of time. Before we even got into pre-production, my friend Rijan and I, who I now run Shway Shway with, collaborated closely on selecting the special pieces that would bring the character to life. Rijan, who grew up in the West Bank, brought so many items straight from Palestine, which we used in the production design.

That felt incredibly special, and I’m so grateful to have had those personal touches in the film. It created a sense of connection, and while only we really knew the significance of those items, we hoped it would still resonate with the audience.

Now that Mawtini (My Homeland) has been released, how has your experience been sharing the film at festivals and within communities both in Canada and beyond?

My relationship with the film has been changing, and wild to say the least. Although Mawtini has just begun reaching audiences, I developed the story long before October 7th and went into production just days after that day. Now, we’re screening a film one year into the genocide, which makes navigating its path forward both challenging and deeply vulnerable. The first screening was with the Canadian Film Centre, the program that funded the project, and it was such a beautiful experience. My community, who supported the film, and friends who poured so much hard work into it, were all there. It was wonderful to celebrate with people who share the same sensibilities and care deeply about the things that matter to you.

I remember that during the credits, someone in the audience chanted “Free, free Palestine!” and the rest of the audience erupted in a call-and-response. I immediately started crying because of how special that moment was.

We then screened Mawtini at Shway Shway Collective, a collective I run with my friend Rijan that screens Palestinian films to raise money for grassroots and on-the-ground efforts in Palestine. One of the groups we raised money for was The Gaza Sunbirds, a team of amputee cyclists who have been delivering food, supporting their communities in Gaza, and doing on-the-ground journalism. Having a space to bring together all of us who are fighting while navigating the genocide and the conversations around it has been both empowering and a source of safety.

How has it felt to witness the many ways audiences have received your film?

It’s been interesting to see the different receptions of the film. But somehow, I always get asked the same question from panels and screenings. No kidding, I’ve been asked this question four times (at one event): “Why did you choose a Palestinian and an Indigenous woman as your main characters for your film?” or something along the lines of “Why did you make this film?” And every time, I was confused that I had to explain it in four different ways.

Has it impacted your relationship with the film?

Going back to what I shared earlier, I tried four different ways to answer the same question. But afterwards, I couldn’t help thinking: Was that a micro-aggression? What is happening? What don’t they get? I’ve already faced challenges navigating the broader film festival landscape, where contradictions and dissonance are overwhelming.

On one hand, these festivals champion “uplifting diverse voices.” But as soon as you mention Palestine or talk about the genocide, they circle back and re-ask the same question, as if they’re waiting for a different answer.

And they’re so good at making it all seem seamless. They’re programming the film, but at the same time, there’s an extent of censorship. Although they’re not censoring my voice outright, but there’s this hesitance and fear to explicitly acknowledge what Mawtini is really about. The film subtly explores these topics but the message is clear. However, I understand that people might have different levels of awareness about the land we’re on, their relationship to Indigenous Peoples, or the situation in Palestine.

Maybe they’re avoiding it altogether.

Where do you think Mawtini stand in adding into this conversation?

I can only hope the film stirs something in them, sticks with them, and eventually makes a connection. If they don’t see it now, inshallah, they will later. The story is there for them to find.

Who is this film for?

I see Mawtini as a gift that I’m offering to the audience—whether they’re aware of what’s going on, unaware, or even choose not to engage with it. How the film is interpreted isn’t up to me, and the process has been eye-opening, almost like a social experiment, watching how different audiences respond. But if I had to define my intended audience, it’s anyone struggling with a connection to home—the displaced, immigrants, second-generation kids, mixed-race individuals, queer folks, and anyone with an intersecting identity that makes the concept of home more complicated.

The word Mawtini is the direct translation for my homeland. Fateema, what is home to you?

That’s a big question. Home for me is very complicated. As a Palestinian living in the west, home feels impossible in a lot of ways. I think through this film, and in my relationship with land here, I’ve realized that there are plants that grow in both Palestine and here—sumac, sage, mint—things that create a small connection to home. I really feel that through my little plants and gardening on my ratty balcony. Home, for me, is in those little pieces, and especially in the people who make you feel like home, no matter where you are.

Where do you go to find anchor and hope as a creative?

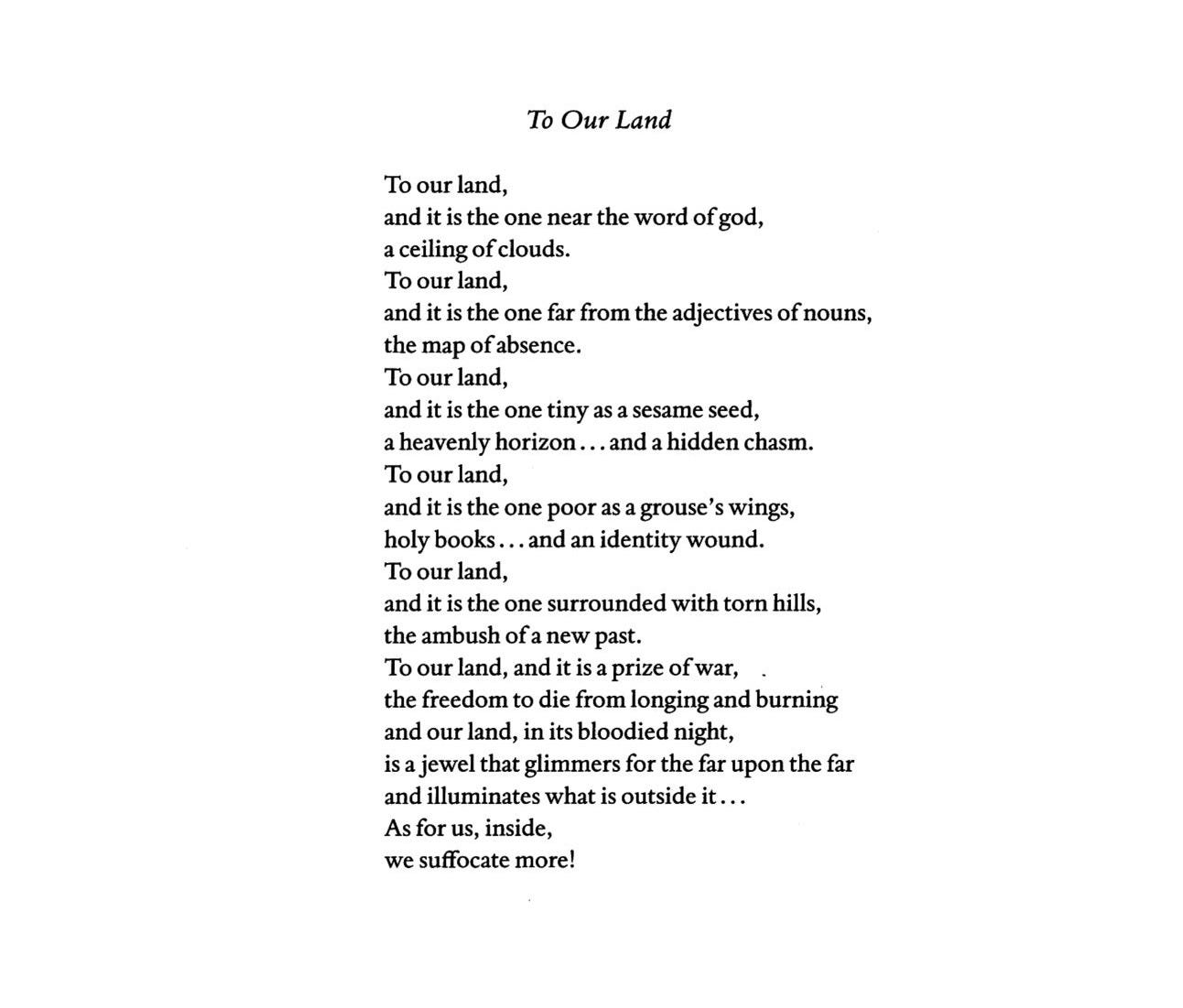

I love the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish. It’s always been a big inspiration for me and something I come back to pretty often. You could start everything with one of his poems because they are so beautiful and powerful. I also feel really inspired by the work of Indigenous creators here, as well as Palestinian filmmakers, both in Palestine and the diaspora.

There's this parallel I see between Indigenous and Palestinian filmmakers, where humour is a thread that runs through our work. People who've endured the most always find a way to laugh—it's a survival mechanism.

I think that’s something that gets lost in the diaspora. A lot of us experience secondhand trauma and intergenerational trauma, but we don’t have that lived experience of what it truly means to endure on the ground. So, I hope that humour continues to live in the work of the diaspora—finding space for both the darkness and the levity.

Do you feel like carrying a sense of responsibility and accountability making art now?

Being Palestinian is a political act, and that comes with responsibility already. This didn’t start for us on October 7th. The context has changed, especially in Palestine now. More than ever, I’m reminded that we need diversity in storytelling. There is so much trauma in the Palestinian experience, and some storytellers have their strength in telling these stories. Some focus on documentaries, following people on the ground; others tell stories of those living under occupation.

Now more than ever, I want to tell human stories. The genocide we’re seeing in Palestine is about dehumanization, and that’s how genocide happens. I feel a responsibility to tell human, complicated stories that show we have so much inside of us, like any other human being. It’s sad that we still have to tell stories just to prove we’re human. From my position, the best I can do with my storytelling is to tell human stories and hopefully wake people up, making them empathize with Palestinian characters. It’s been a nourishing conversation for me.

Does that make you hopeful? Are you hopeful?

It’s really hard to answer this because you’re catching me at a moment where my hope has been really grinded. But I’d say witnessing the world waking up to the genocide for what it is has been incredibly powerful. I’m inspired and hopeful by the resilience of both the Indigenous and Palestinian spirits.

Seeing the world wake up to the realities of the situation in Palestine is something we've never seen in our lifetimes. Despite the immense suffering, people will always find a way to enjoy life. Family and community are so central to our people—Palestinians just want to live, to love, to be together. And seeing that resilience, combined with the global support and voices rising up, has given me hope. We don’t know what the future holds, but we’ve never seen this kind of collective action before.

So, inshallah, I hope it leads to a free Palestine. We can only pray and keep hoping.

FATEEMA AL-HAMAYDEH MILLER: Instagram: @fateemasaurus | Website: Khafeef Dam Productions