Rame Ibrahim & On Holding What Remains.

Filmmaker speaks about recent shorts on Eid (2024) & Prisoner (2025), and unearthing family history through cinema.

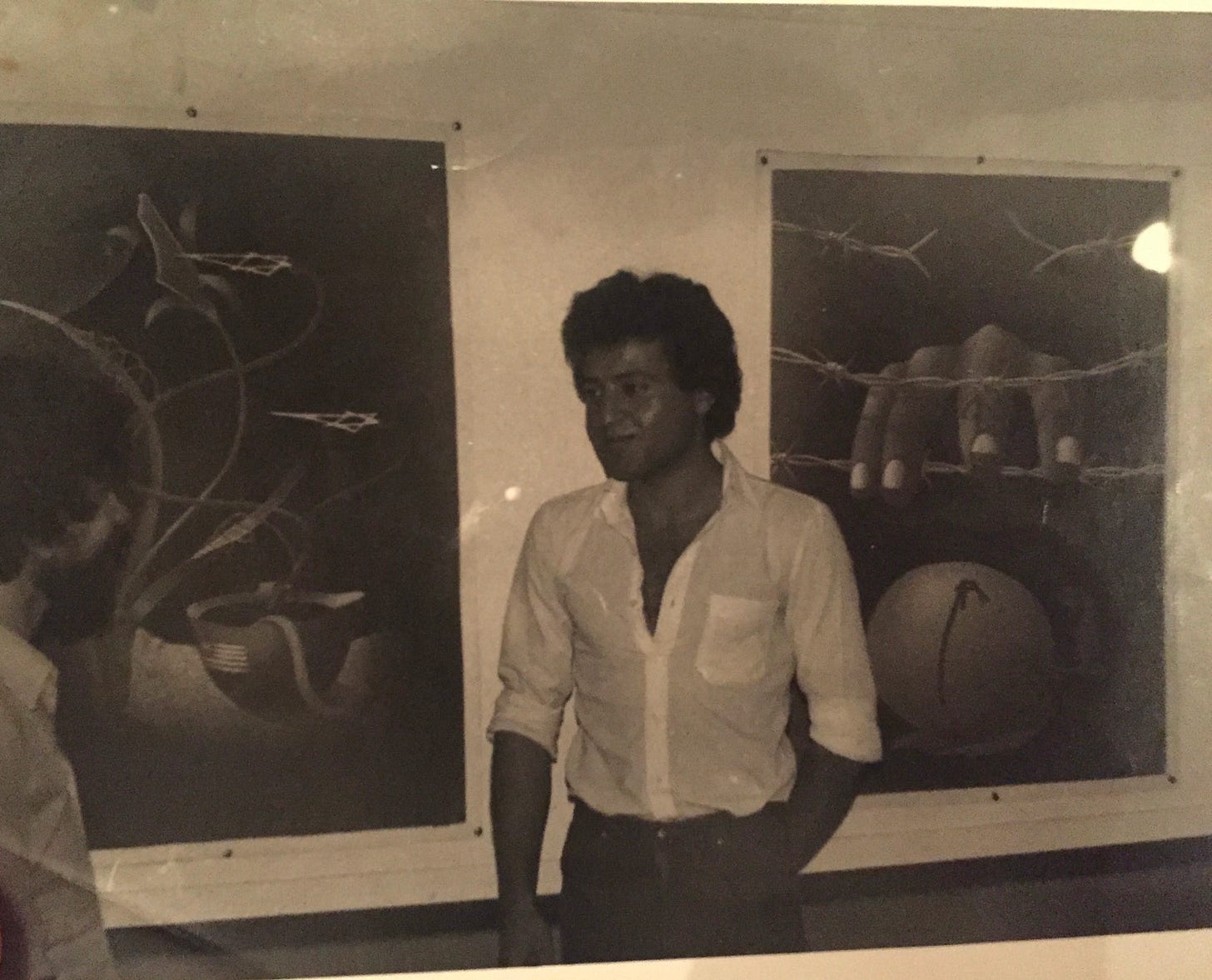

Rame Ibrahim is a Palestinian-Canadian filmmaker whose work transcends borders and emotional arcs, following the facets of grief, memory, and intergenerational love. His short Eid (2024) recently premiered at the Chicago Palestinian Film Festival, while Prisoner (2025), a haunting story of a son uncovering his father’s past as a political prisoner, was shortlisted for the Young Director Award at Cannes Lions. We spoke about the intimacy of silence, staging personal history through cinema, and how Rame’s work holds space for what is both tender and politically charged.

The Produced Media is fully reader-funded and devoted to independent journalism and cultural criticism. Please consider supporting my work with the value of an hour of your time, or whatever you can. Every contribution helps keep the work alive and for more conversation like this. I’m truly grateful for your support - Thanh.

The Produced: Congratulations on the world premiere of your short, Eid, at the Chicago Palestine Film Festival! How are you feeling, Rame?

Rame Ibrahim: Thank you! The festival was beautiful, and Chicago as well. It was wonderful meeting other artists at CPFF,

Eid is such an emotional film to take in. It’s inspired by your paternal uncle, Abdelziz Ibrahim, an artist with the Palestinian Liberation Organization who was killed in an Israeli airstrike. Your grandmother wasn’t able to visit his grave in Jordan, even after trying to repatriate his body to Syria. Growing up, was his story something you were always aware of? What was it like for you in those early stages of developing the story?

I always knew about my uncle as an artist for the PLO, but I didn’t know that my grandma had tried–and failed–multiple times to visit his grave after his murder. Growing up, the details were vague. Later, while brainstorming ideas for my undergrad thesis, my dad shared something he’d written back in Al Yarmouk camp in Syria, and it was about this story. It stuck with me, and I asked if I could develop it further.

I ended up changing his original piece quite a bit, adding new elements to shape it into a script. Through my research, I also uncovered a lot about my uncle’s artwork, most of which is no longer in our family’s possession.

I was reading your interview for the Green College column, “What Can Cinema Do?”, and you mentioned that you’ve always grown up being really conscious of your identity. When you first learned the specifics about your uncle, not just what happened to him but also his role as a poster artist for the PLO, how did that make you feel? And how old were you then?

I don’t think there was a specific moment when I became aware because his presence and legacy were always part of my life growing up. His name always came up in every conversation in the family. So, even though my immediate family moved to the UAE, I spent every summer in Syria at my grandparents’ home, where his artwork was everywhere. There was a statue he made, paintings, photographs. So much of him filled the space. So it wasn’t a conscious realization like, “Oh, my uncle made this.” It was just always there.

Later, you found out that your grandma wasn’t allowed to visit his grave until 2019 because of her refugee status. Until then, she had spent every Eid visiting empty graves, a gesture that says so much about the control over Palestinian bodies, even in death, and how the system continues to separate them from their homeland. When you heard the story from your dad and began turning it into your script, how did you start to process all of these things?

Thank you for this question. What felt very important to me in making this film was capturing something I’ve always felt about my uncle growing up: a PLO poster artist whose work was influential at the time, even if not many know about it today.

When I was developing Eid, I wanted him to be a central part of it, and not just my grandma. Her story ties everything together, but my uncle is the reason I made the film in the first place. Even when the credits roll in Eid, I include all of his artwork as a way to honour him. To keep his presence alive. Those images in the credits are the only copies we have; the original ones are gone, and even reproductions are extremely inaccessible. We’ve been thinking about reaching out to the Palestinian Poster Project in Japan to see if we can recover or find more of his work.

I want my uncle to be remembered, and I attempted to do that through my grandma's story.

What is so acute about your film is the depiction of the way the system governs bodies, not just physically but emotionally and generationally. In the film, it also feels like the mother doesn’t dare dreaming about visiting the actual grave. That restricted movement, on a physical level, starts to shape her dreams, her inner world and her entire lived experience. Was it something you intentionally wanted to highlight in Eid?

Absolutely. My Palestinian family has never returned to Palestine: my grandparents left during the 1948 Nakba, and we grew up in Syria.

What I’m trying to say with the film is that, even though we’ve been physically displaced from the land, the impact of what happens there still carries through generations.

My grandma never had a passport: not then, not now. She left Palestine as a refugee and was only ever issued refugee documents, not a passport. It was the same for the rest of my family. I now have Canadian citizenship, but I didn’t get a passport until I was 15 or 16. Traveling was always difficult. As a child, I didn’t fully understand why. Security checks felt normal: like something everyone had to go through. But as I got older, I realized that constant anxiety around borders and travel was specific to our experience. My dad would get visibly anxious before trips, and now I see that in myself too. Even recently, when I flew internationally, I caught myself bracing for questions at the border.

So, that anxiety around movement becomes something I’ve carried into adulthood. As a kid, I didn’t understand why my parents were always tense around borders. But now, I get it. That feeling has passed on to me, too.

How do you make sense of the film at this moment, now that it’s out in the world? Has your family watched it?

They did. I sent the movie to my dad and family, and I remembered the first viewing was very rough. I don’t want to speak for them, but it felt like it was something that they always wanted to see. Nobody has said anything about my uncle’s death since the airstrike, so showing Eid to my dad and his other siblings was emotional. Everyone was crying. Because it’s a topic that we were revisiting after such a long time, it almost felt like a funeral once again.

Yes, my grandma did get to visit his grave at last, but I don’t know if that was ever going to be satisfactory because the yearning continues.

What about the audience’s reception?

It was such a beautiful experience showing it at CPFF: many people came up to me afterward and shared how much they loved it, which I really appreciated. But I also got the sense that some saw it more as a piece of activism, like I was trying to make a revolutionary statement, rather than as a work of art. Honestly, I’m not sure if that makes sense, and I’m still trying to understand why I felt that way.

What are some of the first feelings or thoughts that came up for you?

In many ways, I think Palestinian art always has to do with the occupation. It’s not because we choose to be activists, but because it’s the life we’re born into. I may not be living directly under occupation, but everything I’ve experienced is shaped by it. My family was forced to leave Palestine during the Nakba and seek refuge in Syria. I’ve searched for a home in the UAE and now in Canada because of it. My uncle was murdered because of it. My grandmother spent decades separated from her son because of it. These are intergenerational consequences.

So for Palestinians, resistance has seeped into our culture and identity not by choice, but by survival. That’s why I think Palestinian art is often seen as activism, rather than art for its own sake. And to be honest, I’m still figuring out how to express that clearly.

Even when we talk about the genocide in Gaza right now, people often praise Palestinians for their resilience. But they don’t want to be resilient: they just want to live their lives without being butchered, bombed, or starved. They are strong because they have no other choice… because they want to live and that’s it.

They love life like anyone else, and I think Palestinian art is much the same. We make films about what we know, just like artists elsewhere.

And as a Palestinian, this is the reality I know, and right now, it’s the most important thing for me to speak about. Sometimes, I find it impossible to write about the occupation because I’ve never lived under the occupation. But what I could talk about is being Palestinian in the diaspora.

And your most recent film, Prisoner, explores the experience of living in the diaspora and being the child of a political prisoner. Could you share more about the heart of the film?

Prisoner is about a father-son relationship: the father was a political prisoner, and the young son, Adam, tries to understand his father’s past through a play he wrote while in prison. It’s based on my relationship with my dad and his experience.

In earlier versions of the script, the focus was on what the father had endured. But as I revised it, I realized I didn’t really know what my father went through as a prisoner. No matter how much I asked, he would never fully share the extent of his experience, and I think that’s a natural parental instinct: to shield their children from pain. Because of that, I knew I wasn’t depicting him correctly.

So, I shifted the story to be told from Adam’s perspective.

What do you mean by not depicting him correctly?

I was imagining what the father might be like: since his past is dark, I assumed he would carry heavy burdens, both physically and mentally. It seemed easier to stick to that familiar theme: an angry man shaped by prison. But my dad wasn’t like that. He’s kind, loving, and caring.

Because of what he’s been through, there are moments when something triggers him to express that pain outwardly. But until then, he often shares his painful memories through humour, making it easier for the child to understand without being overwhelmed by the weight of those experiences.

In Prisoner, Adam learns about his father’s past through a play, which also serves as the film’s narration. This choice grounds the story in Adam’s perspective while offering a deeper look into his father’s life in prison. What led you to structure it this way?

That’s a great question. I initially planned to show the father’s experience in prison through flashbacks. But as I wrote from the child’s perspective, I realized Adam hasn’t seen any of that: he simply doesn’t know what really happened. And, importantly, the father makes sure his son doesn’t see it. The hardest part for a child is having to imagine what his father went through without truly knowing. Including prison scenes wouldn’t feel authentic to the child’s experience, especially since he doesn’t fully grasp the trauma until the very last scene.

For a child, prison is just a place you go when you’re in trouble. You don’t understand what happens there, especially when it concerns someone you love. You tend to dismiss the pain because it’s too difficult to face. But eventually, you begin to notice it. That moment–how Adam comes to understand–is what I wanted to focus on.

Can you share more about your experience directing Prisoner, especially working with the actors?

My actors were incredible. During auditions, I remember seeing the face of the actor who plays Adam’s father and being completely captivated. His face carries so much experience–you can tell he’s lived through a lot, but there’s also a deep kindness in him. It was exactly what Prisoner needed: even when the subject matter is difficult, it still feels like it comes from a place of love.

He understood the character from the very beginning and brought a lot of himself into the role. Coming from the Middle East, he connected with the story on a personal level. We collaborated closely: although much of the script was already written, we spent one to two months rehearsing twice a week and constantly rewriting to find the right balance between showing the father as both a parent and someone shaped by trauma.

One key decision we made was that the father would speak about his trauma through humour, disguising his pain with jokes and a sense of lightness. That became a crucial part of his character and the script. Another important element we developed together was the dynamic between the father and son: they’re not just parent and child; they’re best friends. That tone needed to be established early on, which is why one of the first scenes we shot was of them watching a football match, lying on the couch together and joking around. It sets the foundation for their bond before the emotional weight of the story unfolds.

That’s beautiful. I’m excited for the world to finally see Prisoner. But taking it back to the beginning: how did you first find your way to film as your medium?

I grew up surrounded by art. Both of my parents are writers, my uncle was an artist, I have relatives who are music producers, and my sister plays instruments. So, creativity was always around me.

Initially, I wanted to pursue photography. It was always the thing that spoke to me most. Images felt powerful, as if they could say so much without words. But over time, something shifted. I started noticing that some films were doing exactly what photography did: using the camera to express emotion, atmosphere, and meaning, rather than relying heavily on dialogue. That really changed the way I saw cinema. I realized I could do more with moving images than still ones, even though photography is still very close to my heart. That early influence is probably why I don’t use a lot of dialogue in my work. I tend to lean into the visual language of film because, at the end of the day, that’s what drew me to it in the first place.

For me, art makes life feel coloured and beautiful.

Are you hopeful, Rame?

I think, generally in life, I’ve always had a positive outlook, and a big part of that came from my family. What makes me hopeful is seeing more and more Palestinian artists creating beautiful films, music, and art. I’m also hopeful because there’s a growing recognition of what’s happening in Palestine, even if it’s for bad reasons. I never thought I would see that kind of awareness in my lifetime.

I understand that people are noticing Palestine now because of something horrific: a genocide in Gaza. That should never be the reason, here or anywhere, for people to start paying attention. It’s really sad that this is what it took. I don’t even know if “supportive” is the right word, but people are becoming more aware, and they’re starting to speak up. That gives me some hope.

At the end of the day, I just try to live one day at a time and do what I can. If that ends up meaning something, great. And if it doesn’t, I’ll try again.

The Produced Media is fully reader-funded and devoted to independent journalism and cultural criticism. Please consider supporting our work to for more conversation like this. I’m truly grateful for your support - Thanh.

Stay connected with Rame | Instagram: @ramibrahim99 | Website: rameibrahim.com

For any collaboration, press or sponsorship inquiries, please email Thanh Lieu at info@the-produced.com.

I am one of those who watched all Rami works and I have always felt his high sense.

A deeply moving interview. Rame Ibrahim’s work holds grief, memory, and love with such care. Eid and Prisoner feel like powerful acts of remembrance—personal and beautifully human. Thank you for sharing this.