Trâm Anh Nguyễn & The Softened Gaze.

Multi-hyphenated artist talks honouring familial roots, transness and intersectionality in his work. And of course, on staying hopeful in the hopelessness.

In this article, I’m sitting down with Trâm Anh Nguyễn, a Vietnamese and queer-trans artist I deeply admire. His work beautifully blends poetry, photography, and filmmaking into one seamless craft, breaking through the pervasive nature of retelling narratives. Or, as he puts it, unraveling heavy stories and topics through a softened gaze. His works, including Hoa, Đai Đen trên Núi Bạch Mã, Thân Thể Rừng Thiêng, and to boyhood, i never knew him, have been featured at festivals like TIFF Next Wave, InsideOut Festival, Toronto Queer Film Festival, and in solo and group exhibitions across various spaces.

In this conversation, we talk about two of the most important women in Trâm Anh’s life—his mom and grandmother—and how art has become an indispensable vessel for him to unearth buried conversations and histories. Art, initially a selfish form of expression, turns selfless as it reaches more souls, becoming perhaps the most accurate indicator of one’s transformation: the dreams abandoned and the hopes yet to be fulfilled. This is how Trâm Anh sees his past work as a testament to his growth, both as an artist and as a human being. Lastly, we circled back to the groundedness that film, poetry, and art provide us: a call to respond to one of the most pressing issues in the world—the attacks on trans rights, affecting Trâm Anh’s trans siblings and so many others across America.

Your upcoming film, Mùa Xuân Của Mẹ (Mother’s Spring), follows a Vietnamese teenager assigned female at birth, offering a glimpse into their interior life as they navigate gendered expression, their relationship with their mother, and their heritage.

But as you’ve shared, it’s also an attempt to reconcile with your own personal experiences. What internal process have you gone through to reach this point in making the film? Is it still an internal work in progress?

As a teenager, I held onto a lot of resentment toward my parents. At the time, they weren’t accepting of me, and how I see and define myself. But throughout the years, I’ve seen my mom change in ways I didn’t expect. She makes an effort to understand me and becomes more and more accepting.

Why do you think that is?

Part of it is the distance. Growing up, I was always closer to her despite the tensions in our relationship. But when I moved to Canada at 16, the physical separation shifted our dynamics in some ways. Last year, I returned to Vietnam and lived with her for a year—my first time living with her as an adult. Of course, it’s far from perfect; we still bicker, fight, and get mad at each other. But at the core of it, she has become more open-minded, and I’ve come to see that, above all, my mom just wants me to be happy and safe.

The internal work, for me, has been a lot of reflection. Living with her and seeing her not just as my mom, but as a woman and a fellow adult, has given me a sense of relief and allowed me to see her in a different light.

Has she read the script for the film?

Yes! I actually made the mom character our protagonist, which was an interesting shift. When I read her the script, she laughed and said, “Oh my god, this is exactly what I used to say.”

What were her immediate responses to it?

She was like, “Wait, I’m not the villain, right?” Laughs. By shifting the perspective to the mother, it gave me the space to explore the struggles moms face with change—things they were never really taught in motherhood, at least from what I know.

How do you navigate portraying your mother in a way that acknowledges the impact of your upbringing without vilifying her, avoiding both blame and trauma-dumping?

That’s what I want to be mindful of. Yes, their initial disapproval affected me, but I also recognize that they, too, faced disapproval in their own youth—without resolution—which shaped their own trauma. They’ve endured so much. Being an adult now has also allowed me to foster better dialogues, though that’s not to downplay the weight of childhood experiences. Back then, I was a child, and the power dynamic was undeniable. Now, as an adult, we can engage in these conversations with more trust and balance.

In the script, I’ve written a scene where the mother shares her own upbringing—her experiences, her perspective, the forces that shaped her.

To humanize her.

Yes. To humanize her.

Mother’s Spring isn’t the only film you’ve made about the women in your family. You also created Hoa, a documentary that weaves together poetry, photography, and conversations with your grandmother. What was the starting point of this project?

I had always wanted to make a film about my bà nội—perhaps a traditional documentary with sit-down interviews. But if you watch the film, that’s not how it turned out. Because of her memory loss, she struggled to articulate answers to my questions, so that approach was never possible.

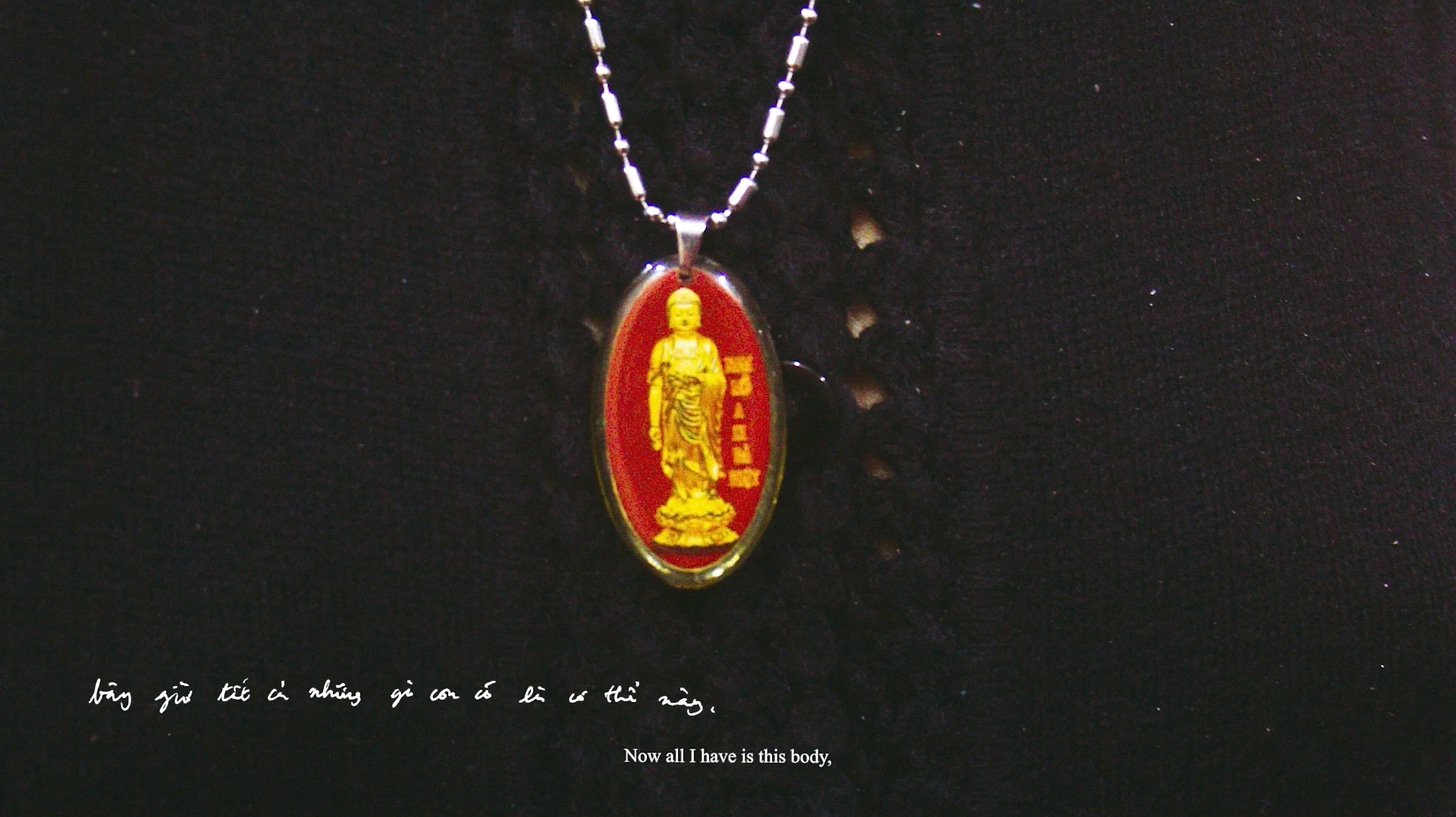

When I visited her in Việt Nam for the last time, I just filmed whatever I could capture of her. Then, after returning to Canada, she passed away almost a year later. Suddenly, all that footage became something else—an unexpected collection of memories. Grieving, I found myself rewatching those clips, each one hitting me harder than the last. The emotions felt too overwhelming to sit with alone, so I turned to journaling, trying to make sense of it all. Those thoughts and words became poems, and eventually, my narration for the film.

With your grandma’s memory loss and her passing, why did you choose to make this film—knowing that, despite it taking the form of a letter to her, your grandma might never see or reach it?

That’s a good question. All I ever wanted was to create something with my grandma. Like I mentioned in the film, the last time I saw her, bà nội had shaved her head—she looked so frail. Before I left for Canada, we said goodbye, with her in her bed and me seeing her without hair for the first time. For some reason, I had this strong feeling it would be the last time I’d see her. And I was right. After she passed, everything came rushing back… the things I wished I had said, the things I wished I had done.

Honestly, I just needed to let it all out. And through this visual form, I was able to express what I couldn’t put into words in real life. Over the years, I had captured so many moments of her—short videos, photographs, quiet observations—and I just wanted to make something out of it. The footage you see in the film was from a time when my family and I didn’t yet know she was at the final stage of her life, that she was developing cancer. It’s just a weird feeling, especially since it’s my first time grieving someone so close to me.

How are you doing now?

I think I’m okay. I actually don’t know. I’m still in that process of learning how to deal with these emotions. But at the same time, it felt like I wasn’t just grieving her. I was also grieving the life I left behind in Việt Nam, all the years I spent growing up there. Losing my grandma just made that loss more clear.

In Hoa, much of your narration speaks to the selfish longing of wanting your grandmother to remember her past, to recount her story, to paint the life she's lived on a blank canvas of fascination, especially in the face of her memory loss and fading health. Why do you think, as grandchildren, we carry this deep fascination with hearing their stories?

As children and grandchildren, we are the continuation of our grandparents’ experiences and the many lives they have lived. Asking my grandma about her life by proxy helps me understand my very being. Deep down, I feel like everything she’s told me and everything I've seen in her eyes, I’ve lived it too.There's something so deep and personal about our grandparents' stories. As kids, especially growing up in Vietnam, I didn't care much about their stories—I just saw them as my grandparents. But as I got older, it hit me that they’ve lived these incredible lives I had no idea about, and now, perhaps, it’s too late to ask them about it.

Was there any conversation, thought or footage that you left out of the film that you wish you had kept?

No, I don’t think so. I think I put in too much. Laughs.

You’ve mentioned that you approach your art through a softened gaze. What does that mean to you, and how does it influence the way you create and interact with the subjects or stories you’re telling?

I think it's just the way I look at the people in my stories like my mom, my dad and my grandma. Even though the subjects we talk about are heavy and carry a silent violence, I try to see them in a soft, gentle way. I always aim to approach it with a softened gaze.

Why is that?

Because no matter how violent or heavy things may seem, there’s also a softness to them. There are moments of peace, gentleness, and stillness, despite everything. I want to balance that. As Vietnamese people, our families carry such traumatic, heavy stories, but I see them differently now.

Do you think approaching trauma and the violence in emotions and memories through a softened gaze and gentleness downplays the weight each individual bears? Children and adults alike?

That’s an interesting point. I always try to address these issues in my art through realism, so I hope it doesn’t downplay them. For me and my art, trauma isn’t the point of the story. I never want my work to feel like trauma-dumping; I aim to approach it from a more realistic perspective. Instead of painting it in purely negative or positive light, it should be presented as a complex issue, showing the multitudes of trauma, its complexities, and the facets we can’t fully pinpoint or reduce to just one thing.

That’s a beautiful answer. How do you think your work reflects the person you were when you created it, and how do you see yourself in those pieces now?

Every work I create reflects who I am at that moment. Looking back, I see I was in a different headspace than I am now. I’m constantly changing, but I’m glad I made those pieces—they captured who I was and what I was going through at the time.

Do you revisit older works that often?

Maybe. I don’t look at my past work with regret, but rather as an interesting reflection of my mindset, thought process, and taste at that time.

From what you've shared, it seems like your art serves both as a personal reflection of your growth, as well as a gift to your intimate community—your parents, your grandparents. Do you feel a sense of responsibility in the world as an artist?

Being called an artist feels strange to me, but I do believe being an artist carries more responsibility than most realize. We live in such a politically charged world, and we cannot exist without each other. Even though I’ve often worked alone, like a one-man team, I couldn’t have created those films without my lived experiences—without the people and the social world around me shaping who I am. I know my work will evolve as I do, but one thing I’m certain of is that art should always be accessible to everyone. As artists, we should use our voices to serve our communities, and I’m always mindful of that responsibility when creating.

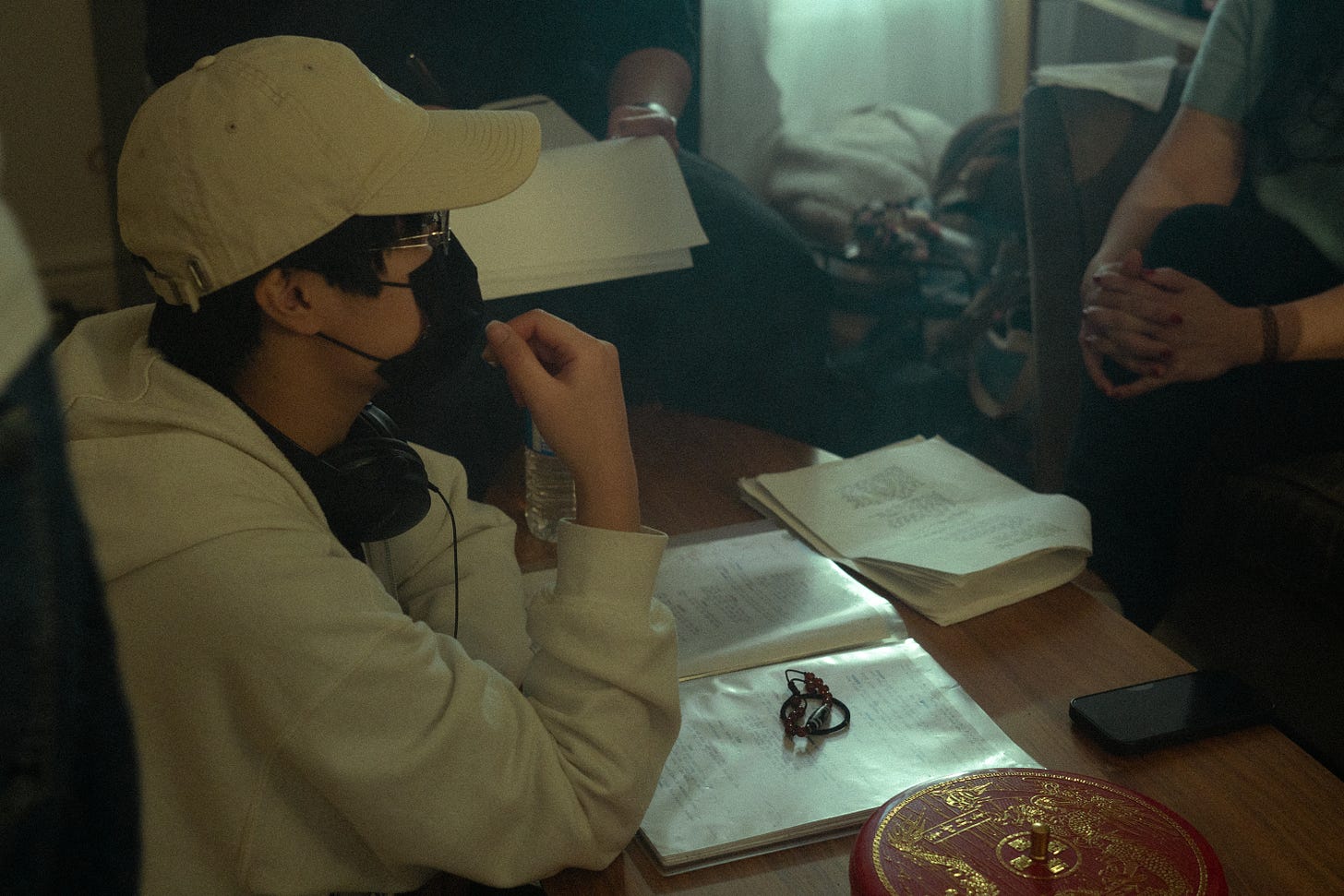

Especially with Mother's Spring, this film felt like a bigger production than anything I’ve done before. For some, it might still be considered a small production, but any crew over five people is a lot for me. Even though it was a student project, being the head of department, the leader, and the director came with a lot of responsibility. I had to be mindful of everyone on set, regardless of how big or small their role was, because everyone contributed to bringing the film to life. Each piece of artwork also carries the responsibility of what it’s trying to say, reflect, or expose about our day-to-day world. It really is a tightly-knit process of communal care and shared responsibility at each stage of creation, and I think it’s crucial to always keep that at the heart of our art.

Your work has always been deeply connected to both your Vietnamese heritage and your trans identity. With the recent political climate in the U.S that directly puts trans folks’ lives at risk, have you reflected on these policies and what are your thoughts on this?

To be honest, every time I see a headline about the harmful rhetoric and policies targeting the trans community, my instinct is to avoid it. I know it’s not healthy, but it becomes so overwhelming that I haven’t reflected on it deeply. I just know I’ll be triggered, so it’s how I’ve been coping. Now that it’s being brought up, my response is simple: it’s just... woah, disappointing. Incredibly disappointing and shocking. I’m shocked at how backwards things are, and how it seems to be getting worse. What I do know for sure is that I’m going to keep doing what I’m doing and continue to stand with my trans siblings in America. They’re always in my heart.

Are you hopeful?

I don’t want to say I’m hopeless, but it does feel a bit hopeless with the current climate and how much negativity has infiltrated our lives—negativity that puts our safety at risk. They want to see us down. They want to see us sad. They want to hide us. But we’re still here, and I know I’ll keep being here.

We’ve always been here.

Trâm Anh Nguyễn: @nghtanh | nguyenhuutramanh.com | films: Hoa, Mùa Xuân Của Mẹ (Mother’s Spring), Black Belts on Bạch Mã Mountain