WITH HASAN IN GAZA, A Conversation with Director Kamal Aljafari.

On cinema as a tool of persistence and resistance against the erasure of memory and Palestinian identity.

An homage to Gaza and its people, to all that was erased and that came back to me in this urgent moment of Palestinian existence, or non-existence. It is a film about the catastrophe, and the poetry that resists.

This is my first film, which I have never made.

These are the words of director Kamal Aljafari on his new documentary, With Hasan in Gaza (2025). In this conversation, Kamal and I discuss the start of his craft in making films with archival materials, the complex nature of memory, cinema as a tool of resistance, and so much more.

With Hasan in Gaza was constructed from three tapes Kamal recorded in 2001 when he visited the Gaza strip. Premiered at the 2025 Locarno International Film Festival and debuted in North America at the 50th TIFF, the film is “dedicated to all those whose lives were violently ended in the struggle for the liberation of Palestine.”

The Produced: You’ve spent 10 years making films from archives and footage that have already existed, including your own from 24 years ago, which appeared in this film, With Hasan in Gaza.

What is like working with materials that have witnessed history and endured time? Something that does not necessarily construct a narrative?

Kamal Aljafari: I came across making films with existing footage totally by chance. My first film that used archives is Recollection, which was released in 2015. With Recollection, I wanted to make a film that showcases Jaffa, a place that no longer exists in reality but is often featured as a backdrop in Israeli and Hollywood films. So, I began collecting footage of these films shot in Jaffa throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Around the same time my ideas for Recollection arose, I was invited to show another film of mine in London, Port of Memory. As I was checking into my hotel, a movie was shown on the TV. I recognized the shot and the place, but I couldn’t recall what the film was. It was Delta Force (1986), starring Chuck Norris. Turns out, it was the exact scene I witnessed as a child during the actual production of the film, in the neighbourhood where my grandparents came from. The whole time I watched it, I just waited for the actors to leave the frame so I could see this place better.

This is when I started working with the idea of collecting all these films and erasing all the characters that were blocking the place they occupy.

What was that process like for you?

Making this film made me realize that cinema can play a role in the reclamation of a place, a narrative, and memory. I found myself caught in a situation where, somehow, these existing films and footage find me.

During my process of collecting these films, I noticed that there were actually civilians in the frame who did not belong to the narrative of these fictional films: the Palestinians who lived in the neighbourhood. They were just passersby or window lookers, observing the crew shooting. Because in these fictional Hollywood and Israeli films, Palestinians did not exist.

Like a blank canvas.

Exactly. I was questioning myself: Why would Israeli film crews choose Jaffa as their film set, especially in the 60s and 70s? It then came to me that they needed Jaffa, an ancient city of more than 5000 years old, to claim a narrative in this country. If they shot their films in Tel Aviv, it would look new, which makes it clear that their existence is new.

When I was watching these movies, I realized that the Palestinians, who were excluded from the narratives of these fiction films, were uprooted twice: first time in reality and second time in cinema. It was important for me then to make a film with these people, who existed at the edge of the frame, in the background, out of focus, where they became the main subject matter of the film.

You recently rediscovered footage you shot in Gaza 24 years ago that later became With Hasan in Gaza. What did you feel when you watched it again?

When I first found the tapes, I didn’t know what it was. The truth is, I never got a chance to rewatch these tapes after shooting them 24 years ago until recently. I took them to a company to play on the player. At first, I only recognized that it was Gaza, but I still didn’t know what I was looking at or why we had filmed it. It was a strange feeling, almost like watching someone else’s memories. Then, suddenly, I saw myself in the footage. That’s when it all started coming back: the trip, the experience of being there. Even now, I’ll admit, I don’t remember shooting all of it. That part is still a mystery to me.

And, that realization alone raises a lot of questions for me about the relationship between memory and images.

That’s so profound. And memory... memory is something that can also trick us.

Totally. Memory is selective: we remember certain things and forget others. In some ways, forgetting can even be a blessing: it can be too much to carry everything at once. Imagine if you remembered everything. Especially in places like Palestine, with such a heavy history, remembering can be overwhelming. In that sense, memory can work against living in the present, against trying to build a new life.

But it’s not something you can control: it comes back to you, it finds you. That’s what happened with this project: the tape had been sitting there all these years, and it came back to me at the moment it was needed.

When I was watching the film, it felt piercingly quiet. All the footage seems to craft its own narrative. I’m curious: when you watched these tapes again and didn't remember that you had shot them, were there any narratives that you were threading in your head? Were there any conscious thoughts of a storyline during that process, for example, which shot came first?

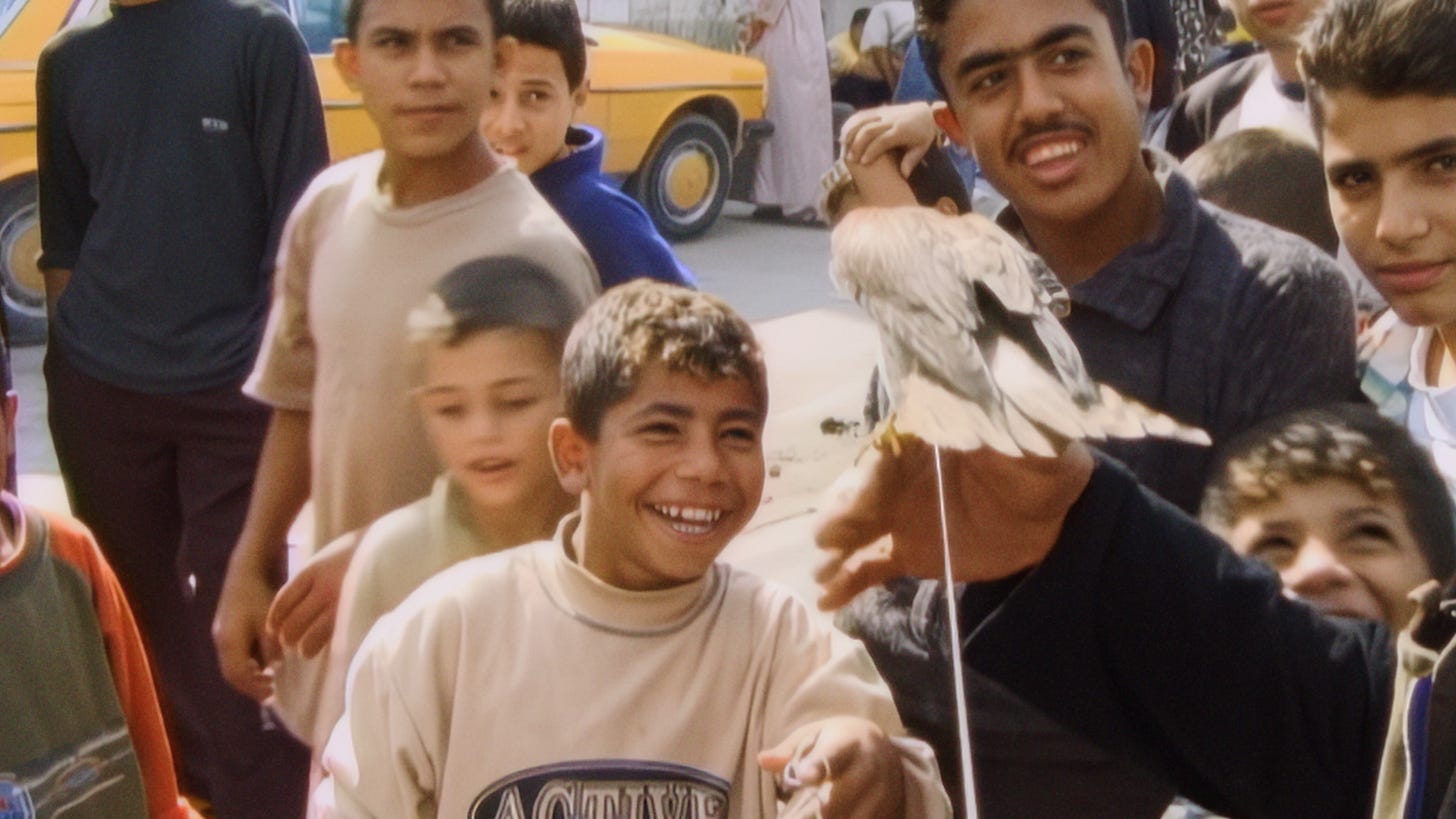

I didn’t want to cut anything, and most of the film is sequenced exactly in the order it was filmed. The three original tapes were about two and a half hours long, and I used almost everything. Some of the moments that struck me most were with the children, who in a way demanded that I film them. There’s one shot where a little girl is calling to me, ‘Photographer, take a picture of me!’

When I did the first test screening before our premiere at Locarno, I teared up. It was so painful and emotional. The children are so innocent: they just want to smile and play, and be seen. And I think that’s how the film works: it connects you back to your own humanity and makes you ask, what happened to these people? Where are they today?

That’s the mystery of cinema: it connects us not only to what we know about Gaza, what has happened and continues to happen there, but also to our shared humanity. That process was very important for me. It kept me positive and hopeful because in the face of this genocide, you feel powerless, like there’s nothing you can do to stop it. People protest, people march in the streets, and yet it continues. Working on this film became a tool that kept me alive, kept me going.

But when I saw it completed, it also confronted me with the reality that the place we see in the footage no longer exists, and that most of the people are now displaced or killed. These are the questions the film carries. So, to answer your question, I had to keep everything, the footage from 24 years ago, as it is.

For me, removing anything would have been painful. It would have felt like a second, third erasure of the Palestinian people.

In an interview, you said this about the film: “It is an homage to Gaza and its people, to all that was erased and that came back to me in this urgent moment of Palestinian existence, or non-existence. It is a film about the catastrophe, and the poetry that resists.”

What do you mean by the film being a catastrophe and a piece of poetry simultaneously? How does that work, and what is that world?

In many ways, filmmaking has been my tool to express myself poetically. I believe poetry has a very tense relationship with memory and the act of remembering. Memory is selective; it comes to us suddenly, unexpectedly. And when it does, we are already somewhere else, already someone else. That condition, for me, creates a very fruitful ground for creation.

And the fact that I’m turning a place that no longer exists or under perpetual destruction into something you can see on screen is already an act of creation, of resistance, a way of freezing time. It feels almost like returning to the origins of cinema and photography.

When you look at cinema this way, especially in relation to Palestine, it becomes a tool of existence, a form of creation that continues even after catastrophe. While making this film, I felt there was life after death. That’s where cinema is most meaningful for me: it can, in some way, defy catastrophe. It preserves the place. Yes, it’s only an image, but it is also evidence.

What do you think the film is saying? Is it a call to attention? Is it a reconstruction of a memory? Is it persistence? And is it all of the above?

It’s everything you’re mentioning. Metaphorically, mostly the children, when they asked me to film them, they were asking for attention and asking to be seen. It’s quite fascinating for me to re-watch this footage again.

You can see that Palestinians, they never get tired of insisting on showing their life and how they live.

It’s painful, but it’s also full of dignity and something beautiful despite all the catastrophes that we have been going through. People insist on maintaining their dignity as human beings. It’s the opposite of what colonizers do, who dehumanize and push people into situations where they have to fight for their lives. I cannot imagine how people can fall asleep in this destructive condition: starvation, drone bombings, not knowing if they will wake up or not. It’s a nightmare.

So, I’m going back to the idea that this film made itself, and it’s an urgent call to attention, of respect, of dignity, and of humanity.

Earlier, you said that revisiting this footage and making this film makes you hopeful. Yet at the same time, the genocide and the reality seem to betray that hopefulness. Are you still holding onto that hope, and what makes you stay afloat to keep holding onto it?

The process of making and creating things keeps me moving forward. Especially in the conditions we are living in, where our very existence is treated like a war, where the idea is that we shouldn’t exist, our voices shouldn’t be heard, there should be no evidence of us at all. You see it in the killing of journalists in Gaza, for example.

What keeps me hopeful, though, is that after making this film, I’ve been able to travel, to connect with people, to have real conversations. I’ve met so many amazing people with their hearts in the right place, and for me that’s such an important sign, that there is still so much beauty in this world, if we can connect to it.

For me, creating every day is part of staying alive. For me, filmmaking is not just a profession you clock into from nine to five: it’s a way of life. You’re in that process all the time. Some people might find it exhausting, but for me it’s what I love, and what keeps me going.

Kamal Aljafari is a Palestinian artist and filmmaker based in Berlin. He studied at the Academy of Media Arts in Cologne and has held teaching positions at The New School in New York and the Deutsche Film-und Fernsehakademie in Berlin. He was awarded a Radcliffe Fellowship at Harvard University and most recently a fellowship at The Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination in Paris (2024–2025).

He has directed the short films Visit Iraq (03), It’s a Long Way from Amphioxus (19), Paradiso, XXXI, 108 (23), and UNDR (24) as well as the features Port of Memory (10), Recollection (15), An Unusual Summer (20), and A Fidai Film (24). With Hasan in Gaza (25) is his most recent work.

Follow The Produced on Instagram. For sponsorship and collaboration inquiries, please email Thanh Lieu at info@the-produced.com